You can’t get a really good look at a used boat or car until you are alone with it. Since I bought the boat in November, I used the off-season winter months for research; I started this article to document what I found...Today, as the boat and information both increase in age, I'm finding that lots of M19 knowledge and lore is slowly disappearing, year by year...

The original owner of my M19 powersailer bought the boat in 1993 in Ohio and sailed her on the upper Chesapeake Bay. It looked like he set it up for for single- or short-handed sailing. He used the boat for over 20 years, then donated it to a maritime museum. I bought the boat in the fall of 2017, and no one knew much more about him or about the boat than that. The best place to find current information on MacGregor powersailers is at the MacGregorSailors.com forum, https://macgregorsailors.com/forum/. There are plenty of comments from 26X and 26M owners, but very little about the M19.

Mast and Standing Rigging

The 23’-8” mast on the M19 is a “two-part” masthead rig and can (theoretically, at least) be stored inside the boat. That is what is shown in the original advertisement and sales brochures and videos of the MacGregor powersailers. What I quickly learned is that "storage" in this case means “end of season” -- or longer-term --storage. It does not mean that the mast is easily dismantled for trailering from point A to point B, or while on the water. A heavy coupling that slides into the mast ends also supports the tubular spreaders and joins the two mast sections. Getting them apart, and back together, is a task that I’m not going to repeat very often (if ever).

The mast cross-section is robust for a 19-foot boat: 4” x 3” (similar to Dwyer DM-6). The stainless steel mast step is hinged. A 3/8-inch bolt is the pivot pin. The step has a second set of holes on the bow end. Presumably these are for the mast-raising gin pole. It does not look like the boom is configured to serve as that element. The lower mast has two cleats for the halyards, but my boat has extra hardware, turning blocks and organizers. They are not original and were added for bringing the halyards back to the cockpit.

There are two flat straps bolted to the forward cabin top corners (below the deck organizer in the photo above). They are original, not added, and are in-line with the mast step. I assume they are the attachment points for the two baby stays that stabilize the mast while it is being raised or lowered. Presumably the ends of the baby stays have special clips that toggle into the straps. There are also two bullet blocks that are toward the forward edge of the cabin top, about 18 inches away from the mast. They are also are original, not added later. Are they fairleads for the jib sheets? Maybe, the owner's manual does not tell. But the manual does show them being used as lashing points for "optional" mast-stabilizing baby stays, which were attached to a set of cleats on the mast that are about five feet up from the step. On my M19 the cleats are only 40 inches up the mast. That's not much stabilizing for a heavy mast that's almost 24 feet long...just sayin'. The mast on my M19 does have two holes, one on each side, further up the mast, about where the alleged cleats would be located. Perhaps a set tangs for connection to the babystays could be attached there, in lieu of another set of cleats.

The mast has upper and lower shrouds that terminate at chain plates bolted to the hull. The chain plates are strong enough to support the boat and were used during assembly in the factory to lift and move the boat around. The shrouds and stays are 1/8-inch 1x19 stainless steel cable with swaged eyes. The lower ends terminate with stainless steel "tang" adjusters, not turnbuckles. Not only are these cheaper devices, but they are, in my opinion, stronger and more reliable on a small boat where the mast is being raised and lowered frequently -- as long as the ring-dings are taped. The forestay carries either the hanked-on a working (100%) or a genoa jib. The M19 has a fixed backstay that is anchored to the aft stainless steel rail above the transom. The mainsheet and the steering is also anchored to this rail, so it’s a pretty substantial structure.

The boom is 8’-6” in length and its cross-section is 3” x 2-⅜” (Dwyer DM-4 is a close match). The gooseneck is 2’-3” above the foot of the mast and the cabin top. When the hatch is open you can stand up in the cabin without hitting your head on the boom. But the clear height in the cockpit is only about five feet. As a result, some M19s have extended masts and raised booms to increase the cockpit clearance.

The M19 owner’s manual specifies that the mast should rake 4 degrees aft. Blue Water Yachts (who provides MacGregor aftermarket parts and support) suggests that the mast rake should be 6-8 degrees (“more than most trailerables”). Raking a mast further aft tends to reduce excess lee helm and improve upwind pointing. The MacGregor manual indicates that the mast rake is correct when a small weight attached to the mainsail halyard should touches the cabin top about 20 inches behind the mast (24 inches equals 5 degrees of rake; 30 inches, 6 degrees; and 40 inches, 8 degrees). The rake is measured with “the boat in the water, the water ballast tank empty, no one aboard, and the weight of a 40-hp outboard on the transom.” I guess you need to be standing at a dock to figure this out.

The forestay and upper shrouds should end up being snug once the rake is set. The backstay is then set tight. The lower shrouds are adjusted to take out any mast curve. The weak point on this rig, according to the owner comments, is are the hinged, tubular aluminum spreaders, which might collapse under load. And many owners upgraded to fixed spreaders with heavier tubing. The bracket for the upgrade, as well as replacement shrouds and stays, appears to be still available from Blue Water Yachts

Sails

Blue Water Yachts (http://www.bwyachts.com/), an aftermarket part supplier for MacGregor sailboats, provides an interesting commentary on the M19 sailplan...

“The 19 is a stiff, stable boat with a fair amount of hull drag and smallish rudders, it wants all the sail power you can put on it. Unless you sail in a very high wind area, almost everyone prefers the balance and performance of the boat with the 150% Genoa. Some very early 1992 models had a simple 3 wire rig with no spreaders and the headstay only about 3/4 of the way up to the masthead. Few of these boats were rigged to run a 150% Genoa, just a tiny 100% Jib. Many of these boats have been re-rigged to the newer masthead rig with spreaders. Sheet winches were an option on the 19, if your boat doesn't have winches on the cabin top, you will need to add them to use a 150% Genoa." (https://shop.bwyachts.com/articles.asp?id=257 )

My M19, built in 1993, has double shrouds and is the masthead rig. I'm sure I've got the original Doyle main sail that came with the boat. The loose-footed mainsail is spec’d at 91 sq-ft and has one reef that is 5-½ feet above the foot, bringing the area down to around 50 sq-ft. On many other boats this reduction in area would be the “second reef” (the first reef being about 12% of the luff length, or 30 inches for this sail). I suspect this was done just to save money at the sailmaker, and because M19 powersailer sailors don't reef. They just fire up the 40-hp outboard and go waterskiing.

The hanked-on working jib, also from Doyle, is specified at 76 sq-ft and is cut with a very high clew to make tacking easier. The sheets are led inside the shrouds through fairleads on the cabin top, then to two single-speed Lewmar 6 winches, and followed by cam-cleats on the cabin-top. The jib does not use turning blocks, and the fixed fairleads are 94 inches aft of the tack on the front of the cabin top, 19 inches off center, giving a theoretical sheeting angle of about 11 degrees. The info provided by Blue Water Yachts suggests that the relatively small jib does not need winches for trimming, and I confirmed that once I had the boat out on the water, but they are nice to have.

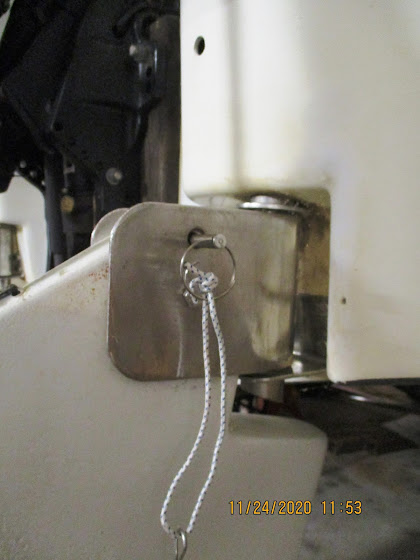

The genoa is 152 sq-ft in area, and the sheets are run outside the shrouds to turning blocks located at the front of the cockpit, then forward to the winches. If there is a cruising spinnaker (which I don't have), the turning blocks are relocated to the rear of the cockpit, temporarily strapped to the aft mooring cleats. A lot of owners added a track on the cockpit rail to accommodate an adjustable block. I can’t see that ever happening on my M19 unless I decide to play with a light-air screecher some day in the future.

Replacement sails, as well as other parts for the M19, appear to be still available from Blue Water Yachts. When I bought the boat you could also get new sails from Hyde Sails (who also supplied sails for the Potter sailboats). They showed a 97 sq-ft mainsail, a 105 sq-ft No. 3 jib, a 123 sq-ft No. 2 genoa, and a 137 sq-ft No. 3 genoa. Unfortunately, Hyde is not longer building sails for MacGregors, or for Potter boats...To borrow a phrase from Kurt Vonnegut's "Slaughterhouse Five," so it goes. You can still buy a sail kit from Sailrite and then build it yourself.

Running Rigging

The halyards were led through turning blocks at the base of the mast, through a couple of deck organizers on the cabin top corners, then aft to Spinlock cam-cleats. In addition to the stock cam-cleats that followed the jib winches, there was an extra set of cam-cleats.

And the centerboard was rigged to operate from the cockpit with a third Spinlock cam-cleat. The mainsail has luff slides to make it easy to get tie sail up and down the mast track. The hanked-on non-furling jib had been set up with a positive “downhaul” line, as evidenced by the guide attached to the bow pulpit and to the forward cabin top. And there was a “tiller tamer” at the helm. These are many of the same changes that I made on my Potter to make it easier to sail single-handed. And buying the M19 already set up for single-handed operation saved a lot of effort and money. I still have not figured out why there is an extra set of cam-cleats around the winches, and these will be removed.

In any event, I could not detect that any kind of quickie reefing was set up, although the boom has a hook at the tack, and the outhaul could be reset through the reef cringle on the leech (if you have the time and crew to do it, and the conditions are not too wild). You could probably set up a reef on the dock, and then shake it out, but it would be a pain to put the reef in if there was any serious breeze. The boat does have the optional vang to control sail twist, but only a rudimentary outhaul to adjust the sail flatness. In typical frugal MacGregor fashion, the outhaul consists of a cleat on the end of the boom. The original owner had added a Harken lazy-jack system (a plus!), which is consistent with the single-handed set-up for the halyards, the jib downhaul, and the centerboard.

Centerboard and Rudder

As mentioned Part 1, a weak point on the M19 and 26X powersailors, which have centerboards, is their centerboard pendant and pulley -- something I neglected to check during my initial inspection. The board raising system consists of a multipart pulley system on the cabin floor that is connected to a stainless cable pendant. Notice, in the photo below, that the centerboard control line runs up the mast. There is another turning bullet block near the cabin top, and then the line heads aft, above the door to the "head", to a Spinlock cleat just inside the hatch opening. Theoretically it is possible to set the centerboard from the cockpit. Turns out there is a lot of resistance in a couple of 90-degree changes using regular braid rope, and this mod needs some work.

Before I settled the purchase I did climb under the boat to inspect and verify that the pennant and lower pulley were in good shape. The centerboard is hollow and has fill holes so that the centerboard does not float. Once the boat is out of the water with the centerboard up, the water inside drains right out. There are warnings in the owner's manual and prominently posted on the boat that the centerboard must be raised if motoring more than 5 mph.

On the cabin floor there are two round ports that provide access into the ballast tanks. You can see one of them in the photo above. They also provide access to the centerboard pivot bolt and the pennant pulley attachment. Here's a drawing from the owner's manual showing what's down there.

The M19 has a very narrow motorwell, and the outboard can be turned only a few degrees off center, so the rudders do most of the steering under both sail and under power. The M19 is unique because the rudders are short and fairly thick and it is steered from a traditional tiller, not a wheel like the 26X and 26M powersailers. The tiller-to-rudder articulation is located well above the transom top, and a common complaint is “sloppy steering.”

As I inspected my boat, I found that rudder tiller arm brackets did not fit the rudder posts. A 1/4-20 bolt was used for attachment, but the brackets rocked on the rudder post, and they needed to be shimmed.

All of the MacGregor powersailers have twin kick-up rudders. The kick-up rudder blades are hinged on custom stainless steel rudder posts, shown in the photo below.

The kick-up mechanism used on the M19 is probably one reason why MacGregor sailboats are frequently characterized as "cheaply built." MacGregor incorporated sacrificial plastic shear pins, or nylon bolts, to hold the hinged blades in the down position. The photo below shows the rudder blade down, with the stainless steel "transport" pin (normally used to lock the blades up for trailering).

Running aground breaks the pin, like a fuse in an electrical system, and hopefully protects the steering mechanism and rudder blade. But it's now impossible to steer the boat. And how do you replace it when you're out on the water? And furthermore, the shear pins must be strong enough to keep the rudders down while planing at full speed (according to the specs, up to 25 mph), but still able to shear through if you hit something solid. On the shallow Chesapeake Bay, I did not expect the pins to last very long; and several spares -- clearly homemade replacements -- were included with the boat. Re-designing the kick-up rudders would be on the top of the list.

Outboard and Prop

The M19 is specified for outboards up to 40 hp, and my boat had a 1995 Mercury with electric start, electric lift and an alternator. This outboard is a two-cycle engine with oil injection. The water pump impeller and oil pump impeller were both replaced during the summer, just before I bought the boat.

The outboard came with a 10-1/4x14 prop. The shop that serviced the outboard said that prop was very likely the stock prop that came with the outboard back in 1995. There's a lot of discussion on the forums (a good one to look through is on MacGregorSailors.com, https://macgregorsailors.com/forum/viewforum.php?f=7) on the best replacement outboards for the MacGregor 26 powersailers, and the "correct" prop seems to be endlessly debated. What is clear, however, is that all of MacGregor powersailors require lower pitch props. Owners indicate that their boats wind up being propped like a big pontoon boat with lots of drag. If the pitch is too high, the engine will never run efficiently (or hit it's rated "WOT" -- wide open throttle rpm spec), it will run slow (due to excess slippage), have poorer gas mileage (for the same reason), and will "speed" at low rpms -- just when you want to crawl into a slip -- with the extra bite. One of the first changes I made was replacing the 14-inch pitch with a 12-inch pitch prop. And that is probably still too high, based on subsequent comments from the motor tech. And I will need to add a tachometer to figure this out.

Accouterments

The cabin hatch cover is hinged, not a slider. Pull the hinge pins and it is removable. On a mooring, that would be a nice feature. Be forewarned -- the cover weighs about 25 pounds and it will probably sink to the bottom if it gets away. Some M19 owners modified their hatch covers to act like the "pop tops" that were fairly common on many of the smaller O'Days and Catalinas, and even some Hunters, with cabins.

The original wiring for the cabin and navigation lights is a well-known weak point for MacGregors -- and for many other boats built more than 20 years ago. It looked like lamp cord, and nothing was fused. The previous owner re-located the battery from a compartment amidship to a shelf in the "head" and added a bilge pump in one of the aft storage compartments, just ahead of the transom. M19’s were not shipped with bilge pumps -- the bilge is occupied with the water ballast tank, and the fill channel runs down the middle to a gate valve on the transom. It's not clear what the pump was doing, but water had gotten back there at some point.

The motor well drains to a thru-hull fitting on the starboard side above the waterline. The hose connecting the motor well drain and the outlet had a tee for the output of the bilge pump. There was no gate valve on outlet, and the hoses had single hose clamps.

The boat came with a single 8-pound Danforth anchor with 10 feet of ⅜-inch chain, and 70 feet of ½-inch nylon rode. The rest of mooring setup was stock: one mooring cleat on the foredeck and one on each side of the stern. The Mac powersailers did not come with anchor line chocks up forward, and many owners added them. The previous owners installed a nice bimini the covered the cockpit, but it was too big to work with the sail rig and was removed. Adding usable shade is near the top of the list.

My M19 doesn't have and apparently never had a boarding ladder. If I ended up overboard, I would have to try to climb back up on the rudders or the outboard. I feel that this potential hazard needs to be addressed without too much delay. The factory ladder was a custom design, but still looks like Blue Water Yachts can provide one for about $300. The boat did come with a vintage porta-potti. I don't think it had ever been used (the "head" is not very big); I immediately removed it from the boat and stuck it in a corner of my shop. Let me know if you need one to complete your MacGregor restoration project and need OEM parts.

The boat came with the original trailer, also built by MacGregor. For a 20-year old steel trailer, it was in pretty good shape. I suspect that it was stored indoors when it wasn't being used. Maybe it hadn't been used much if the owner kept the boat in a slip during the sailing season. The lights had been replaced with LED tail lights. As I mentioned in Part 1, I replaced the tires and wheels as a matter of routine if they are more than five years old.

Sailing

Searching the internet, I found useful information what to expect once I got the boat out on the water (see, https://macgregor.sailboatowners.com/reviews.php?mid=158 ). The experience of M19 owners indicated that the boat sails very poorly under main alone, and is difficult to sail upwind even in good winds (not too surprising considering that motorsailing upwind is where the outboard becomes very useful). Because the high cabin top results in significant windage, this boat struggles to sail through the wind unless care it taken to time the tack through the waves. Like a catamaran, the jib can be backwinded to force the bow over. By the same analysis, reefing the mainsail will reduce heel but will make tacking even more difficult if there is no headsail. So a storm jib might be a valuable addition if reefing is anticipated. The boat will perform much better if it is not sailed close to the wind, and unless the water is flat, one should probably bear off just prior to a tack to get enough power to make it through the wind. Unless the route is primarily a reach or run, the best hanked-on headsail will be a small jib that can easily tack inside the forestay triangle. Any larger headsail will require help to get across. A roller-furler and headsail designed for adjustable area is a high-priced alternative (similar to a screecher that you roll in the sail each time you tack).

No comments:

Post a Comment